Using WebAssembly for Extension Development

May 8, 2024 by Dirk Bäumer

Visual Studio Code supports the execution of WASM binaries through the WebAssembly Execution Engine extension. The primary use case is to compile programs written in C/C++ or Rust into WebAssembly, and then run these programs directly in VS Code. A notable example is Visual Studio Code for Education, which utilizes this support to run the Python interpreter in VS Code for the Web. This blog post provides detailed insights into how this is implemented.

In January 2024, the Bytecode Alliance launched the WASI 0.2 preview. A key technology in the WASI 0.2 preview is the Component Model. The WebAssembly Component Model streamlines interactions between WebAssembly components and their host environments by standardizing interfaces, data types, and module composition. This standardization is facilitated through the use of a WIT (WASM Interface Type) file. WIT files help describe the interactions between a JavaScript/TypeScript extension (the host) and a WebAssembly component performing computations coded in another language, such as Rust or C/C++.

This blog post outlines how developers can leverage the component model to integrate a WebAssembly library into their extension. We focus on three use cases: (a) implementing a library using WebAssembly and calling it from extension code in JavaScript/TypeScript, (b) calling the VS Code API from WebAssembly code, and (c) demonstrating how to use resources to encapsulate and manage stateful objects in either WebAssembly or TypeScript code.

The examples require that you have the latest versions of the following tools installed, alongside VS Code and NodeJS: rust compiler toolchain, wasm-tools, and wit-bindgen.

I also want to say thank you to L. Pereira and Luke Wagner from Fastly for their valuable feedback on this article.

A Calculator in Rust

In the first example, we demonstrate how a developer can integrate a library written in Rust into a VS Code extension. As previously mentioned, components are described using a WIT file. In our example, the library performs simple operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. The corresponding WIT file is shown below:

package vscode:example;

interface types {

record operands {

left: u32,

right: u32

}

variant operation {

add(operands),

sub(operands),

mul(operands),

div(operands)

}

}

world calculator {

use types.{ operation };

export calc: func(o: operation) -> u32;

}

The Rust tool wit-bindgen is utilized to generate a Rust binding for the calculator. There are two ways to use this tool:

-

As a procedural macro that generates the bindings directly within the implementation file. This method is standard but has the disadvantage of not allowing the inspection of the generated bindings code.

-

As a command line tool that creates a bindings file on disk. This approach is exemplified in the code found in the VS Code extension sample repository for the resources example below.

The corresponding Rust file, which uses the wit-bindgen tool as a procedural macro, appears as follows:

// Use a procedural macro to generate bindings for the world we specified in

// `calculator.wit`

wit_bindgen::generate!({

// the name of the world in the `*.wit` input file

world: "calculator",

});

However, compiling the Rust file to WebAssembly using the command cargo build --target wasm32-unknown-unknown results in compile errors due to the missing implementation of the exported calc function. Below is a simple implementation of the calc function:

// Use a procedural macro to generate bindings for the world we specified in

// `calculator.wit`

wit_bindgen::generate!({

// the name of the world in the `*.wit` input file

world: "calculator",

});

struct Calculator;

impl Guest for Calculator {

fn calc(op: Operation) -> u32 {

match op {

Operation::Add(operands) => operands.left + operands.right,

Operation::Sub(operands) => operands.left - operands.right,

Operation::Mul(operands) => operands.left * operands.right,

Operation::Div(operands) => operands.left / operands.right,

}

}

}

// Export the Calculator to the extension code.

export!(Calculator);

The export!(Calculator); statement at the end of the file exports the Calculator from the WebAssembly code to enable the extension to call the API.

The wit2ts tool is used to generate the necessary TypeScript bindings for interacting with the WebAssembly code within a VS Code extension. This tool was developed by the VS Code team to meet the specific requirements of the VS Code extension architecture, mainly because:

- The VS Code API is only accessible within the extension host worker. Any additional worker spawned from the extension host worker lacks access to the VS Code API, which contrasts with environments like NodeJS or the browser, where each worker typically has access to almost all the runtime APIs.

- Multiple extensions share the same extension host worker. Extensions should avoid performing any long-running synchronous computations on that worker.

These architectural requirements were already in place when we implemented the WASI Preview 1 for VS Code. However, our initial implementation was manually written. Anticipating broader adoption of the component model, we developed a tool to facilitate the integration of components with their VS Code-specific host implementations.

The command wit2ts --outDir ./src ./wit produces a calculator.ts file in the src folder, containing the TypeScript bindings for the WebAssembly code. A simple extension that utilizes these bindings would look like this:

import * as vscode from 'vscode';

import { WasmContext, Memory } from '@vscode/wasm-component-model';

// Import the code generated by wit2ts

import { calculator, Types } from './calculator';

export async function activate(context: vscode.ExtensionContext): Promise<void> {

// The channel for printing the result.

const channel = vscode.window.createOutputChannel('Calculator');

context.subscriptions.push(channel);

// Load the Wasm module

const filename = vscode.Uri.joinPath(

context.extensionUri,

'target',

'wasm32-unknown-unknown',

'debug',

'calculator.wasm'

);

const bits = await vscode.workspace.fs.readFile(filename);

const module = await WebAssembly.compile(bits);

// The context for the WASM module

const wasmContext: WasmContext.Default = new WasmContext.Default();

// Instantiate the module

const instance = await WebAssembly.instantiate(module, {});

// Bind the WASM memory to the context

wasmContext.initialize(new Memory.Default(instance.exports));

// Bind the TypeScript Api

const api = calculator._.exports.bind(

instance.exports as calculator._.Exports,

wasmContext

);

context.subscriptions.push(

vscode.commands.registerCommand('vscode-samples.wasm-component-model.run', () => {

channel.show();

channel.appendLine('Running calculator example');

const add = Types.Operation.Add({ left: 1, right: 2 });

channel.appendLine(`Add ${api.calc(add)}`);

const sub = Types.Operation.Sub({ left: 10, right: 8 });

channel.appendLine(`Sub ${api.calc(sub)}`);

const mul = Types.Operation.Mul({ left: 3, right: 7 });

channel.appendLine(`Mul ${api.calc(mul)}`);

const div = Types.Operation.Div({ left: 10, right: 2 });

channel.appendLine(`Div ${api.calc(div)}`);

})

);

}

When you compile and run the above code in VS Code for the Web, it produces the following output in the Calculator channel:

You can find the full source code for this example in the VS Code extension sample repository.

Inside @vscode/wasm-component-model

Inspecting the source code generated by the wit2ts tool reveals its dependency on the @vscode/wasm-component-model npm module. This module serves as the VS Code implementation of the component model's canonical ABI and draws inspiration from corresponding Python code. While it's not necessary to comprehend the internals of the component model to understand this blog post, we will shed some light on its workings, particularly regarding how data is passed between JavaScript/TypeScript and WebAssembly code.

Unlike other tools such as wit-bindgen or jco that generate bindings for WIT files, wit2ts creates a meta model, which can then be used to generate bindings at runtime for various use cases. This flexibility allows us to meet the architectural requirements for extension development within VS Code. By using this approach, we can "promisify" the bindings and enable the running of WebAssembly code in workers. We employ this mechanism to implement the WASI 0.2 preview for VS Code.

You might have noticed that when generating the binding, functions are referenced using names like calculator._.imports.create (note the underscore). To avoid name collisions with symbols in the WIT file (for example, there could be a type definition named imports), API functions are placed in an _ namespace. The meta model itself resides in a $ namespace. Thus, calculator.$.exports.calc represents the metadata for the exported calc function.

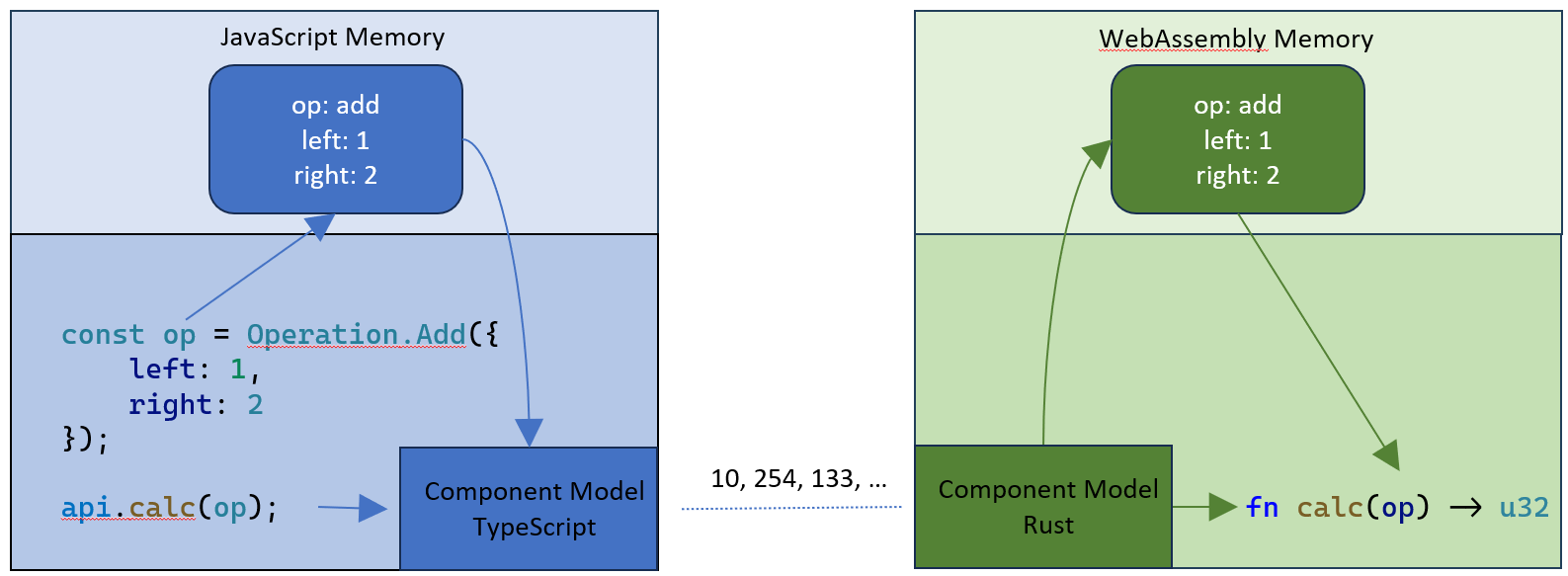

In the above example, the add operation parameter passed into the calc function consists of three fields: the operation code, the left value, and the right value. According to the component model's canonical ABI, arguments are passed by value. It also outlines how the data is serialized, passed to WebAssembly functions, and deserialized on the other side. This process results in two operation objects: one on the JavaScript heap and another in the linear WebAssembly memory. The following diagram illustrates this:

The table below lists the available WIT types, their mapping onto JavaScript objects in the VS Code component model implementation, and the corresponding TypeScript types used.

| WIT | JavaScript | TypeScript |

|---|---|---|

| u8 | number | type u8 = number; |

| u16 | number | type u16 = number; |

| u32 | number | type u32 = number; |

| u64 | bigint | type u64 = bigint; |

| s8 | number | type s8 = number; |

| s16 | number | type s16 = number; |

| s32 | number | type s32 = number; |

| s64 | bigint | type s64 = bigint; |

| float32 | number | type float32 = number; |

| float64 | number | type float64 = number; |

| bool | boolean | boolean |

| string | string | string |

| char | string[0] | string |

| record | object literal | type declaration |

| list<T> | [] | Array<T> |

| tuple<T1, T2> | [] | [T1, T2] |

| enum | string values | string enum |

| flags | number | bigint |

| variant | object literal | discriminated union |

| option<T> | variable | ? and (T | undefined) |

| result<ok, err> | Exception or object literal | Exception or result type |

It is important to note that the component model does not support low-level (C-style) pointers. As such, you cannot pass object graphs or recursive data structures. In this respect, it shares the same limitations as JSON. To minimize data copying, the component model introduces the concept of resources, which we will explore in more detail in a forthcoming section of this blog post.

The jco project also supports generating JavaScript/TypeScript bindings for WebAssembly components using the type command. As mentioned earlier, we developed our own tooling to meet the specific needs of VS Code. However, we hold bi-weekly meetings with the jco team to ensure alignment across the tools wherever possible. A fundamental requirement is that both tools should use the same JavaScript and TypeScript representations for WIT data types. We are also exploring possibilities to share code between the two tools.

Calling TypeScript from WebAssembly code

WIT files describe the interaction between the host (a VS Code extension) and the WebAssembly code, facilitating bi-directional communication. In our example, this feature allows the WebAssembly code to log traces of its activities. To enable this, we modify the WIT file as follows:

world calculator {

/// ....

/// A log function implemented on the host side.

import log: func(msg: string);

/// ...

}

On the Rust side, we can now call the log function:

fn calc(op: Operation) -> u32 {

log(&format!("Starting calculation: {:?}", op));

let result = match op {

// ...

};

log(&format!("Finished calculation: {:?}", op));

result

}

On the TypeScript side, the only action required from an extension developer is to provide an implementation of the log function. The VS Code component model then facilitates the generation of the necessary bindings, which are to be passed as imports to the WebAssembly instance.

export async function activate(context: vscode.ExtensionContext): Promise<void> {

// ...

// The channel for printing the log.

const log = vscode.window.createOutputChannel('Calculator - Log', { log: true });

context.subscriptions.push(log);

// The implementation of the log function that is called from WASM

const service: calculator.Imports = {

log: (msg: string) => {

log.info(msg);

}

};

// Create the bindings to import the log function into the WASM module

const imports = calculator._.imports.create(service, wasmContext);

// Instantiate the module

const instance = await WebAssembly.instantiate(module, imports);

// ...

}

Compared to the first example, the WebAssembly.instantiate call now includes the result of calculator._.imports.create(service, wasmContext) as a second argument. This imports.create call generates the low-level WASM bindings from the service implementation. In the initial example, we passed an empty object literal since no imports were necessary. This time, we execute the extension in the VS Code desktop environment under the debugger. Thanks to the excellent work of Connor Peet, it is now possible to set breakpoints in the Rust code and step through it using the VS Code debugger.

Using Component Model Resources

The WebAssembly component model introduces the concept of resources, which provide a standardized mechanism for encapsulating and managing state. This state is managed on one side of the call boundary (for example, in TypeScript code) and accessed and manipulated on the other side (for instance, in WebAssembly code). Resources are extensively used in the WASI preview 0.2 APIs, with file descriptors being a typical example. In this setup, the state is managed by the extension host and accessed and manipulated by the WebAssembly code.

Resources can also function in the reverse direction, where their state is managed by the WebAssembly code and accessed and manipulated by the extension code. This approach is particularly beneficial for VS Code to implement stateful services in WebAssembly, which are then accessed from the TypeScript side. In the example below, we define a resource that implements a calculator supporting the reverse Polish notation, similar to those used in Hewlett-Packard hand-held calculators.

// wit/calculator.wit

package vscode:example;

interface types {

enum operation {

add,

sub,

mul,

div

}

resource engine {

constructor();

push-operand: func(operand: u32);

push-operation: func(operation: operation);

execute: func() -> u32;

}

}

world calculator {

export types;

}

Below is a simple implementation of the calculator resource in Rust:

impl EngineImpl {

fn new() -> Self {

EngineImpl {

left: None,

right: None,

}

}

fn push_operand(&mut self, operand: u32) {

if self.left == None {

self.left = Some(operand);

} else {

self.right = Some(operand);

}

}

fn push_operation(&mut self, operation: Operation) {

let left = self.left.unwrap();

let right = self.right.unwrap();

self.left = Some(match operation {

Operation::Add => left + right,

Operation::Sub => left - right,

Operation::Mul => left * right,

Operation::Div => left / right,

});

}

fn execute(&mut self) -> u32 {

self.left.unwrap()

}

}

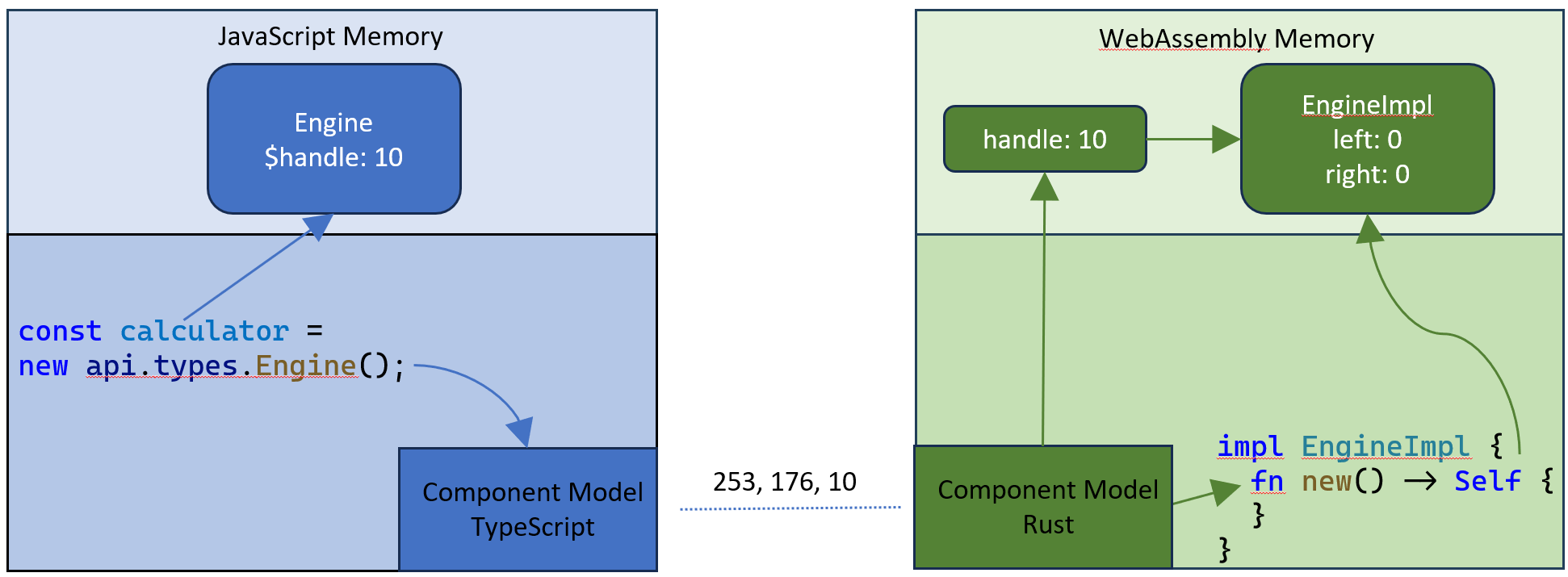

In TypeScript code, we bind the exports in the same manner as before. The only difference is that the binding process now provides us with a proxy class used to instantiate and manage a calculator resource within the WebAssembly code.

// Bind the JavaScript Api

const api = calculator._.exports.bind(

instance.exports as calculator._.Exports,

wasmContext

);

context.subscriptions.push(

vscode.commands.registerCommand('vscode-samples.wasm-component-model.run', () => {

channel.show();

channel.appendLine('Running calculator example');

// Create a new calculator engine

const calculator = new api.types.Engine();

// Push some operands and operations

calculator.pushOperand(10);

calculator.pushOperand(20);

calculator.pushOperation(Types.Operation.add);

calculator.pushOperand(2);

calculator.pushOperation(Types.Operation.mul);

// Calculate the result

const result = calculator.execute();

channel.appendLine(`Result: ${result}`);

})

);

When you run the corresponding command, it prints Result: 60 to the output channel. As mentioned earlier, the state of resources resides on one side of the call boundary and is accessed from the other side using handles. No data copying occurs, except for the arguments passed to methods that interact with the resources.

The full source code for this example is available in the VS Code extension sample repository.

Using VS Code APIs directly from Rust

Component model resources can serve to encapsulate and manage state across WebAssembly components and the host. This capability allows us to utilize resources to expose the VS Code API canonically into WebAssembly code. The advantage of this approach lies in the fact that the entire extension can be authored in a language that compiles to WebAssembly. We have begun to explore this approach, and below is the source code of an extension written in Rust:

use std::rc::Rc;

#[export_name = "activate"]

pub fn activate() -> vscode::Disposables {

let mut disposables: vscode::Disposables = vscode::Disposables::new();

// Create an output channel.

let channel: Rc<vscode::OutputChannel> = Rc::new(vscode::window::create_output_channel("Rust Extension", Some("plaintext")));

// Register a command handler

let channel_clone = channel.clone();

disposables.push(vscode::commands::register_command("testbed-component-model-vscode.run", move || {

channel_clone.append_line("Open documents");

// Print the URI of all open documents

for document in vscode::workspace::text_documents() {

channel.append_line(&format!("Document: {}", document.uri()));

}

}));

return disposables;

}

#[export_name = "deactivate"]

pub fn deactivate() {

}

Notice that this code resembles an extension written in TypeScript.

Although this exploration appears promising, we have decided not to proceed with it for now. The primary reason is the lack of async support in WASM. Many VS Code APIs are asynchronous, making them difficult to proxy directly into WebAssembly code. We could run the WebAssembly code in a separate worker and employ the same synchronization mechanism used in the WASI Preview 1 support between the WebAssembly worker and the extension host worker. However, this approach might lead to unexpected behavior during synchronous API calls, as these calls would actually be executed asynchronously. As a result, the observable state could change between two synchronous calls (for instance, setX(5); getX(); might not return 5).

Moreover, efforts are underway to introduce full async support to WASI in the 0.3 preview timeframe. Luke Wagner provided an update on the current state of async support at WASM I/O 2024. We have decided to wait for this support, as it will enable a more complete and clean implementation.

If you're interested in the corresponding WIT files, the Rust code, and the TypeScript code, you can find them in rust-api folder of the vscode-wasm repository.

What Comes Next

We are currently preparing a follow-up blog post that will cover more areas where WebAssembly code can be utilized for extension development. The major topics will include:

- Writing language servers in WebAssembly.

- Using the generated meta model to transparently offload long-running WebAssembly code into a separate worker.

With a VS Code idiomatic implementation of the component model in place, we continue our efforts to implement the WASI 0.2 preview for VS Code.

Thanks,

Dirk and the VS Code team

Happy Coding!